Uriah, with his long hands slowly twining over one another, made a ghastly writhe from the waist upwards, to express his concurrence in this estimation of me.

Uriah Heep is a character in Charles Dickens’ novel “David Copperfield”. I think he is one of the most disgusting persons as a character in a book you can think of. He is vile, scheming behind people’s backs – all the while pretending to be ‘humble’, submissive and grateful. In the story’s reality he is practically the opposite. He makes use of secrets to his own advantage, using blackmail to gain power over others. But in that story it takes almost a decade until his true character and his deeds are known – and redeemed.

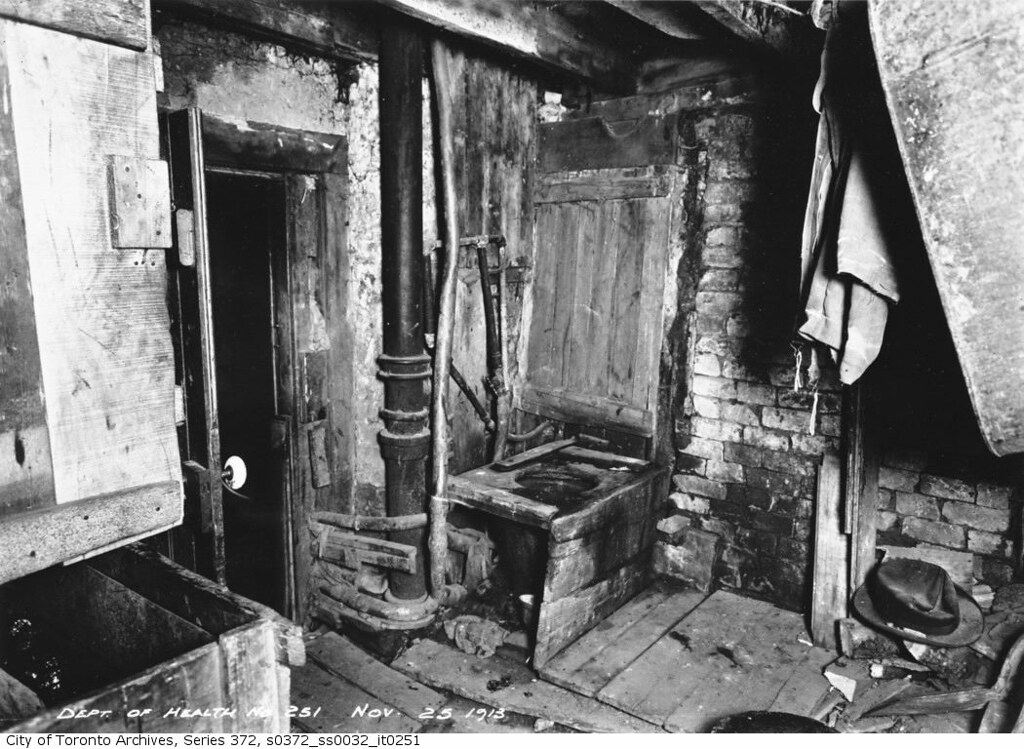

Although in English literature many of Dickens’ novels are counted among the romances to some extent due to the highly emotional parts – they are very realistic in the depiction of living conditions in the first half of the 19th century. The extreme poverty and starvation that included dreadful living conditions in London slums are the locations Dickens’ uses for famous and most influential stories such as “Great Expectations”, “David Copperfield” or “Oliver Twist”. Dickens was a wonderful master of the language, of dramatic point and counterpoint – and the plot as such, clear, including dramatic twists and turns as well as a true feeling for the unfortunate that make his books great examples of the rising civil societies’ best values: Empathy and social security as well as justice.

I was raised on firm principles: I do not believe that business and its representatives are the ruling powers of this world. So many people writhe and grovel for the sake of a favour, even if only inwardly, of a job, their character becoming so warped and twisted that its original quality becomes invisible. It’s sad to watch when you meet them.

I was raised to the idea that trade unions had been created for a reason. That every human being as such is what is called ‘a small universe’ in some contexts. That the capital in the hands of the few will not stay there or be ‘multiplied’ if the many ‘little people’ do not work for that.

Additionally, I was raised on an explicit work ethic: And an understanding of the many connections as well as relations that make human life what it is – and that make it necessary and desirable in a reasonably sensible business to do the best in my ability to make that business thrive – and keep mine as well as others’ jobs – to an advantage.

My approach is not always clear and easy to everyone around I know. There are still parts of this world where the belief in the ultimate authority of anyone superior in a hierarchy make it crucial to be subdued, even servile, in everyday behaviour. Anyone deviating from that kind of behaviour may be subjected to suspicions of disloyalty.

For me these two views are worlds apart:

-

-

Be ‘a humble servant’. Or

-

be a proud, self-contained and yet reliable employee and/or colleague in an honourable trade.

-